Since we first published an article about the use of venous stents to treat pseudotumor cerebri last year, the story has been widely shared on social media. The interest is especially high among one group in particular: patients diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), an inherited connective tissue disorder.

EDS patients typically experience a range of very challenging symptoms, from hypermobility and joint instability to venous insufficiency. If the growing number of EDS patients inquiring about venous stenting is any indication, it appears intracranial venous stenosis is also extremely prevalent in this subset of patients.

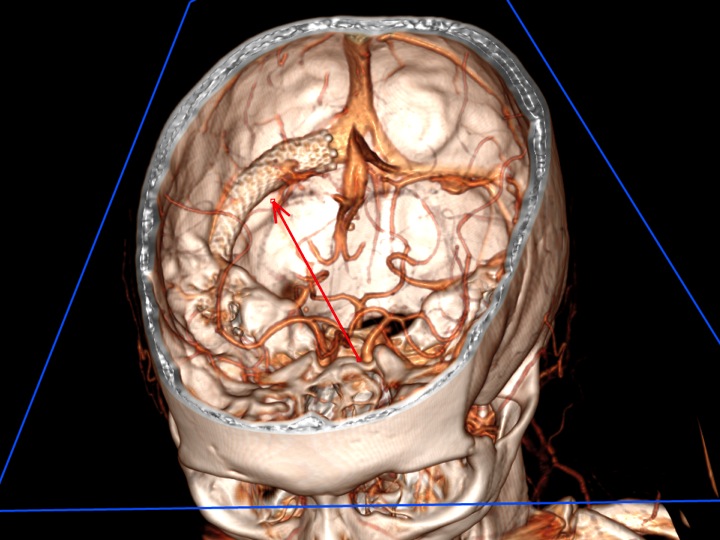

“We identified some EDS patients who were very puzzling to neurosurgeons,” says UVA Director of Neurovascular Surgery Kenneth Liu, MD. “We found that for whatever reason, the veins in their brain were clogged, causing blood to back up and pressure to increase in the brain.”

Because UVA is one of the few centers offering endovascular venous stent placement to treat intracranial venous stenosis, EDS patients from as far away as Kuwait and Australia have reached out to Liu in hopes of relieving their symptoms, the most common being what they describe as “brain fog.” Pamela Fenner, a 46-year-old mother of two from Glen Allen, Va., experienced this sense of slow thinking and impaired memory along with other symptoms that were much more debilitating. “My vision was affected. I had headaches, a whooshing sound in my ears and weakness in my arms; I couldn’t even pick up dishes to put them away in the cabinet,” she says. “It was starting to slow me down.”

Like many EDS patients, Fenner had multiple procedures over the years, including a spinal fusion and posterior fossa decompression surgery, but she felt there were no good options presented to her that would relieve the pressure in her brain. “I was on medication for four years and then I was told I could have a shunt implanted in my brain, but that requires maintenance so I didn’t want to do that,” she says.

As her symptoms worsened, Fenner sought out other alternatives. “I saw an article on Facebook in a group for others with this condition. It had Dr. Liu’s email, so I reached out to him. He got back to me within five minutes,” Fenner says.

Last summer, Liu met with Fenner and two other EDS patients, each of whom were experiencing a range of symptoms resulting from intracranial venous stenosis. “I had long conversations with each of these patients,” says Liu. “We decided to do the stent procedure and see what happened. I told them, ‘We don’t have any proof that this works, but I’m willing to try it.’ I’ve done hundreds and hundreds of stents in the brain, but these were the first in this patient population. This is really brand new.”

Fenner was the first to undergo the minimally invasive stenting procedure. “I was ready to do whatever it took based on my symptoms,” she says. “At the same time, I would be the first one with Ehlers-Danlos to undergo the stent procedure, and we don’t have the best blood vessels. But I trusted Dr. Liu and I felt it was riskier to do nothing because the veins were so blocked. I had transverse sinus stenosis — the left side was 90 percent blocked and the right was 75 percent blocked.”

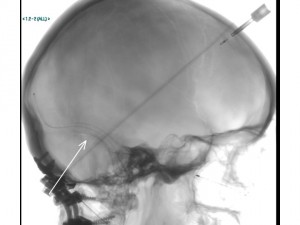

Through two small needle pokes in the groin, Liu was able to successfully thread a stent into Fenner’s left transverse sinus, shown in the X-ray image at left. Once the normal flow of blood exiting the brain was restored, pressure within the skull dropped and Fenner experienced immediate relief. “The blurry vision was gone immediately, and I’ve been headache free since the procedure,” she says. “I’ve gotten my strength back, the whooshing in my ears is gone and my memory has improved. I’m cautiously optimistic.”

According to Liu, Fenner was not the only EDS patient to experience drastic results. “We had one patient who hadn’t walked for two years; she had a very mild vein narrowing,” he says. “We put the stent in and two days later she was walking. Two days after that, she was running on the treadmill.”

While not all outcomes have been this extreme, Liu says the EDS patients he’s treated thus far have all seen positive improvements. The challenge for Liu is explaining exactly why these patients are improving to this degree.

“We believe we’re improving the flow of blood,” says Liu. “But compared to other cases of stenosis, the brain pressure in these Ehlers-Danlos patients is much more subtle. There has to be something to measure scientifically to prove something is better or different after the intervention. We haven’t found that magic thing yet, but clinical trials may be down the road.

“As a physician and scientist, I still don’t know what to believe,” he adds. “Maybe this is all placebo effect.”

For EDS patients, it seems the only thing that matters is that venous stenting is offering relief from debilitating symptoms. “Word is spreading,” says Liu. “And I haven’t turned anyone away.”

Liu has performed the venous stenting procedure on more than 50 EDS patients thus far and he keeps close tabs on their progress, with regular clinic follow-ups and email correspondence. “We don’t know how long the effect of the stent will last. It’s only been about 10 or 15 years since we started putting stents in brain, so the concrete data we have is limited,” says Liu. “I hope they last for the rest of their lives.”

Learn more about venous stenting to treat pseudotumor cerebri.

If you have specific questions about intracranial venous stenosis in EDS patients, please contact Kenneth Liu.