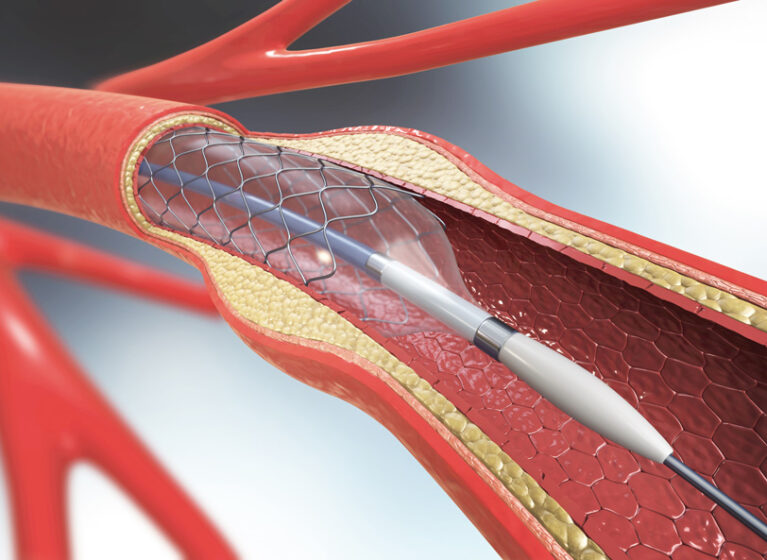

Re-opening a stented artery that has developed stenosis again from plaque or scar tissue has long been a challenge for interventional cardiologists.

Traditional therapies for treating coronary in-stent restenosis (ISR) in patients with coronary artery disease have included placing additional metal stents, balloon angioplasty, and radiation therapy (i.e. brachytherapy). These treatments aren't always effective or can lead to particular complications, like increasing the risks for thrombosis or future ISR.

However, the FDA has approved a new, more effective method for treating ISR, using a drug-eluting balloon. UVA Health is the first, and currently only, medical center in Virginia to use this new therapy with patients, and is one of only a select few centers in the U.S. with this offering.

Used properly, this technology helps prevent restenosis and the need for additional stents. This is critical because the more layers of stents patients receive, the more likely ISR will occur and the harder it is to treat.

While the use of drug-coated stents in the past two decades has reduced the incidence of restenosis, rates are still relatively high: roughly 10% generally, and as high as 20% in certain populations (such as patients with diabetes or renal failure).

Game-Changing Technology

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug-coated balloon in March 2024. The approval came on the heels of a clinical trial, called AGENT IDE, that enrolled 600 patients with ISR across 40 U.S. centers. Its findings: a paclitaxel-coated balloon was statistically superior to an uncoated balloon for target lesion failure at 12 months. And, target vessel-related myocardial infarctions and cardiac deaths occurred less often in the coated versus uncoated balloon groups.

Angela Taylor, MD, an interventional cardiologist and Professor of Medicine at UVA Health, was the principal investigator for the AGENT IDE trial. “This new technology is the first of its kind in the U.S. For cardiologists and, more importantly, for patients, it is probably the biggest game changer in interventional cardiology in several years,” says Taylor.

Unique Features of Drug-Eluting Balloon

Following proper preparation, the paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter is inserted either through the radial or femoral artery. It’s then guided to the affected coronary stent, where it delivers a therapeutic dose of the drug to the diseased artery wall to help prevent future restenosis.

According to Taylor, the design of the drug-eluting balloon makes it an excellent delivery system. “Paclitaxel is hydrophobic, so we can put it through the guide catheter into the bloodstream without the drug coming off. And, because it is also lipophilic — meaning it dissolves in fats and lipids — it accelerates absorption into the artery wall and enables us to deliver the drug directly to the place we care about, which is inside of the stent.”

Another advantage, notes Michael Ragosta, MD, also an interventional cardiologist and Professor of Medicine at UVA Health, is that, unlike other drugs whose molecular shapes are typically round spheres, this drug has a crystalline structure. That helps it stick to the artery wall.

Thorough Preparation is Critical

The success rate of this procedure depends on how well the artery is prepared before the cardiologist delivers the drug-eluting balloon.

Three criteria must be met beforehand:

- Patients must have less than 30% residual angiographic stenosis.

- Lumen size must be 80% or greater compared to the distal reference vessel.

- Patients must have excellent blood flow as measured by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade.

Taylor, who travels to medical centers across the country to train cardiologists on using this new method, says that almost all candidates can meet these three criteria “if cardiologists are dedicated to spending the time necessary to get the artery ready for the balloon.”

“This is very different than the traditional concept of ballooning,” adds Ragosta. “The drug eluting balloon is strictly a drug delivery mechanism. It’s the last and easiest part of the procedure.”

Analyze Why Restenosis Occurred

To optimize your success rate, it is critically important to understand why stenosis is again developing in the patient’s artery and then address it.

There are typically three reasons:

- The stent wasn’t fully expanded because it was improperly placed initially

- Overgrowth of scar tissue forming within the stent

- New cholesterol build-up inside the stent

“The latter is essentially disease progression which is unrelated to the stent,” notes Taylor. “More commonly, ISR results from the first two reasons.”

Use of Ultrasound is Key

When training catheterization lab staff and physicians around the country about this new balloon procedure, Taylor emphasizes the importance of using intravascular ultrasound to diagnose stent failure and determine treatment options. Ultrasound can help identify conditions within artery, such as calcium build-up along the artery wall. The cardiologist would then attempt to address those conditions, like breaking up the calcium, before proceeding.

Drs. Taylor and Ragosta cite the advantages of ultrasound over angiograms. “Angiograms, which cardiologists have long used as a diagnostic tool, just give us a two-dimensional view of the lesion,” says Taylor.

“When you do an ultrasound,” says Ragosta, “you view the artery from the inside and see the entire artery in cross-section. You can see much more clearly whether the stent is fully expanded or whether it is crimped in one spot. The stent may look good according to the angiogram, but not when viewed by the ultrasound.”

Adds Taylor: “Many cardiologists don’t realize the value that ultrasound imaging provides. There’s a knowledge gap. There’s also a steep learning curve in interpreting the ultrasound.”

Training Reduces the Need for Restenting

One of the goals of educating and training cardiologists about this new technology, says Taylor, is to encourage them to use intravascular ultrasound when they first place stents in patients.

“Ultrasound should be a regular part of the process, but today, probably less than half of interventional cardiologists routinely use ultrasound,” says Taylor. “We aim to change that. Using ultrasound for the initial stent placement can result in decreased ISR, heart attacks, and death.”