University of Virginia neuroscientist George Bloom, PhD, studies how Alzheimer's disease develops biochemically in order to improve the prognosis for those at high risk for this debilitating condition. Based on some of his recent findings, UVA Health clinicians have launched a pilot study involving an approved drug with the potential to do just that.

Building Blocks of Plaques & Tangles

Bloom has focused for many years on understanding the underlying processes that lead to neuron death and the subsequent behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer's with the goal of developing an effective therapeutic.

"What we're most interested in is, at a cellular and molecular level, what happens at the very beginning to convert normal, healthy neurons into Alzheimer's neurons — and just as importantly, how to leverage what we learn by our basic-science approach to clinical translation," Bloom says.

Over the course of more than a decade, Bloom and other researchers established that the insoluble plaques and tangles (the hallmarks of Alzheimer's) are not its primary cause. Rather, it is the soluble building blocks of these structures — amyloid beta for plaques and tau for tangles — that work together to damage brain function.

"We were not the first lab to notice a pathogenic connection between amyloid and tau, but we have dedicated much of our work for the last 15 years to unraveling those connections," Bloom says. "We've been studying several phenomena that mimic what we think is happening in Alzheimer's brain."

Deciphering Neuron Death in Alzheimer's Disease

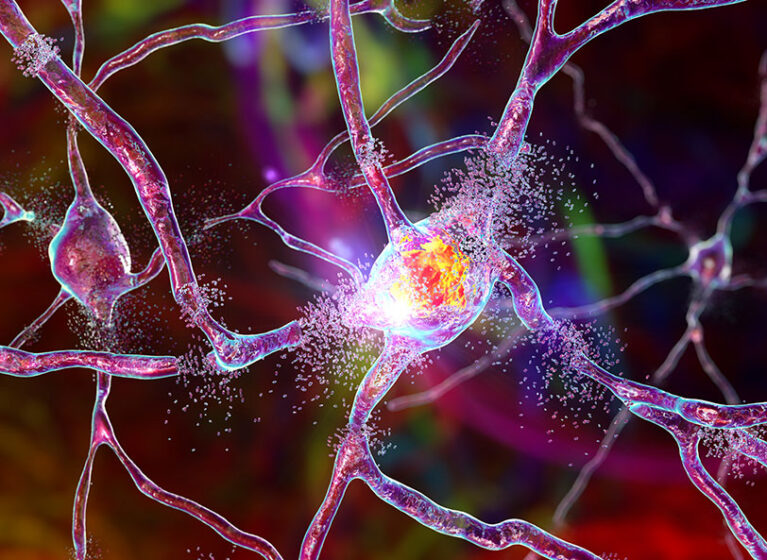

Bloom and his colleagues have demonstrated that in Alzheimer's brain, some neurons re-enter the cell cycle abnormally. The atypical cell-cycle re-entry process can be initiated by simply exposing neurons to amyloid beta peptides. Toxic forms of amyloid beta, called amyloid beta oligomers, cause healthy tau to unfold and convert into a form that kills neurons and causes synapse failure, resulting in cognitive decline.

"In Alzheimer's, there's an extended period — maybe 10 or 20 years — when neurons re-enter the cell cycle but never divide," Bloom explains. "Instead, they die a year or so after. This may account for as much as 90% of the neuron death that takes place in Alzheimer's."

In recent work published in Alzheimer's & Dementia, Bloom and others revealed another cause of abnormal cell-cycle re-entry in Alzheimer's patients: an influx of excess calcium into neurons stimulated by amyloid beta oligomers via a defective neurotransmitter receptor known as NMDA.

Early Action to Prevent Irreversible Brain Damage

The processes underlying neuron death begin decades before people experience symptoms of Alzheimer's. "That's the ideal therapeutic window, rather than waiting until people become symptomatic," he says. "By that point, massive irreversible brain damage has occurred."

One promising approach to this challenge is to prevent amyloid beta from converting tau to toxicity in the first place. Bloom's work has shown that memantine, an FDA-approved drug used to treat moderate to severe Alzheimer's, prevents abnormal neuronal cell-cycle re-entry in the brains of transgenic mice that mimic human Alzheimer's disease and in cultured neurons. These findings make memantine a prime candidate for testing in people long before Alzheimer's symptoms arise.

UVA Health's Carol Manning, PhD, a neuropsychologist and director of the UVA Health Memory Disorders Clinic, recently took up the research baton from Bloom's group. Together, they launched a pilot study designed to explore the feasibility of a larger study to test memantine's efficacy in delaying symptom onset and/or slowing symptom progression when given to patients before symptoms are evident.

From Basic Research to the Real World

Manning's double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial will involve 10 to 32 people. To participate, people must:

- Be 50 to 65 years old

- Have a first-degree relative with the disease

- Carry the ApoE4 allele

- Have normal cognition

During the 2-year study, the UVA team will follow patients, including monitoring their cognitive and behavioral changes every 6 months. A private family foundation is funding the project.

"Memantine currently is indicated for people in moderate stages of Alzheimer's disease," Manning says. "Dr. Bloom's animal work indicates that is way too late in the disease state. What is exciting is that he has evidence that indicates if you give it before symptoms begin, you can hopefully change the trajectory — and even prevent symptoms — of Alzheimer's."

Although the pilot study is modest, Bloom hopes it will eventually lead to a prophylactic solution. He envisions a scenario in which people at high risk for Alzheimer's will receive a preventive drug or combination of drugs at least a decade before expected symptom onset.

"It would be similar to how we now commonly use statins to protect against eventual cardiovascular disease," he says.