Thirty percent of the liver transplants performed at UVA Health are for the treatment of liver cancer. Care for these patients is multifaceted and involves a team of specialists who take an oncology approach to treatment, providing ongoing surveillance and support even when patients come from distant places. UVA is one of the only comprehensive transplant centers in the state, so transplant specialists are accustomed to partnering with referring physicians in other cities to provide the long-term care required for these patients.

“We communicate openly with a patient’s care team back at home so that we can monitor their condition from afar,” says transplant surgeon Shawn Pelletier, MD. “If we notice any problems, then we can arrange for patients to be seen here at UVA.”

Below is a case study for one Richmond patient with a very rare cancer who required a liver transplant to prevent further disease progression.

Patient: Leslie Waller, 33-year-old female

Presented with: Upper abdominal pain that was confirmed by her local provider to be a symptom of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEH), a rare type of liver cancer that is most common in women ages 20 to 30.

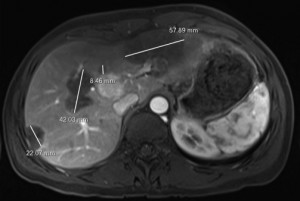

“She had an ultrasound and CT  scan that showed multiple lesions in her liver,” says Pelletier. “The assumption was that these could be benign lesions; however, after approximately six months, tests showed that the lesions were increasing in size. If they were benign, they would not grow. A biopsy then confirmed the cancer diagnosis.”

scan that showed multiple lesions in her liver,” says Pelletier. “The assumption was that these could be benign lesions; however, after approximately six months, tests showed that the lesions were increasing in size. If they were benign, they would not grow. A biopsy then confirmed the cancer diagnosis.”

Evaluated by: Once the diagnosis was confirmed, Waller was referred to Pelletier.

Treatment: According to Pelletier, the first line of treatment for HEH is liver resection. “If we can remove the tumor successfully, then the patient can live normally,” he says. However, only around 20 percent of patients with HEH are candidates for this approach. After reviewing scans taken over the course of two months, Pelletier determined that Waller’s cancer was growing quickly and there were numerous tumors throughout her liver. Thus, her only treatment option was liver transplant.

Unfortunately, suspicious areas on Waller’s lungs put the treatment plan on hold briefly. A lung biopsy was performed, but the results were inconclusive. “If she did have a malignancy in the lungs, then the immunosuppressants given after transplant could make other types of cancer besides HEH metastasize faster,” explains Pelletier. “However, because HEH metastases grow very slowly despite immunosuppression, we decided to move forward. If this had been a different tumor, we may not have made that choice.”

Preparation: Waller met with a multidisciplinary team of UVA transplant specialists, including a transplant hepatologist, social worker, transplant coordinator, neuropsychologist, financial counselor, nurse educator and others who helped evaluate her readiness for transplant and ensure she was a good candidate for the procedure. “The entire process, which included imaging of the liver and staging of her cancer, took approximately six to eight weeks,” says Pelletier. Then, once Waller agreed to the procedure, she was put on the wait list to receive a new liver.

“For organ allocation, those with cancer are given extra points and move up the list because, even though they may not die of liver failure, if their cancer spreads, they lose the potential to get a transplant,” says Pelletier. “For this very rare type of cancer, however, we had to submit a written exception to all centers in the region and we were not certain they would approve. For this reason, we began looking at living donors as well.”

Waller’s husband was shown to be a match, but before he could complete the evaluation process, an organ from a deceased donor became available. Waller had been on the wait list for approximately three months.

Procedure: Once the deceased donor was confirmed, Pelletier traveled to the donor hospital to perform the organ procurement procedure, which lasted approximately two hours. Once inspected, the organ was packaged and transported back to UVA. “The cold time for a liver is approximately eight hours,” says Pelletier.

Upon Pelletier’s return, the surgical team, including David Bogdonoff, MD, director of Liver Transplant Anesthesia, prepared Waller for surgery. She had four different IVs, including large volumes of fluids and blood products in case there was bleeding, as well as a dose of immunosuppressants. Her pulmonary artery pressures were monitored throughout. Pelletier made an incision in Waller’s right upper quadrant to remove the liver and gallbladder. The donor liver was then removed from the cooler and positioned for implantation.

Pelletier performed the inferior vena cava, hepatic arterial and portal anastomoses. Upon reperfusion of the liver, the liver anesthesiologist was on hand to resuscitate if necessary but was not needed in this case. There were no complications. “The point of reperfusion is the most dangerous,” says Pelletier. “If bleeding is going to happen, that is likely when it will occur.” With reperfusion successful, Pelletier then performed the bile duct anastomosis and closed the incision.

Recovery: For the first 24 hours after the transplant procedure, Waller’s kidney and liver function were monitored carefully and she was watched closely for any signs of bleeding. She was given a second dose of immunosuppressants (tacrolimus, mycophenolate and steroids) to help prevent organ rejection. “Most recipients continue to take one drug — tacrolimus — for life,” says Pelletier. “In Mrs. Waller’s case, she takes a low dose of tacrolimus as well as everolimus, which has immunosuppressant as well as antineoplastic effects.”

On day six after surgery, Waller was discharged home. “Most liver transplant patients have chronic liver disease, so they require nutritional supplements, physical therapy and remain in the hospital for around 10 days post-transplant,” says Pelletier. “Mrs. Waller did not require any additional therapy and recovered more quickly than average because she came in relatively healthy and she was asymptomatic.”

Follow-up: Surveillance scans of the chest and abdomen have shown no signs of recurrence. The original chest lesions remain unchanged and liver function is normal. A Richmond resident, Waller was under the care of Bon Secours transplant hepatologist Mitchell Shiffman, MD, in Hampton Roads. “Dr. Shiffman is very experienced and can take care of her routine transplant needs,” says Pelletier. “We speak with him weekly to discuss Mrs. Waller’s case as well as a variety of other patients. We communicate openly and get patients back to UVA if needed. This collaboration allows us to ensure they’re doing well without requiring them to commute to UVA.”

For more information about referring a patient to UVA Transplant Center, contact our Physician Relations team.